linkedin users revolutionize cringe, again

If we boiled down LinkedIn to a one word description, it's cringe, but why and how does it come to be?

Estimated reading time: 18 minutes“The hallmark of the age of cringe is that there’s always a performance going on, and social media is the stage.”

– The Atlantic

If you ask me, there isn't a better embodiment of cringe than LinkedIn, the crown jewel of performative professionalism. If social media is a stage, LinkedIn is the over-enthusiastic actor who keeps forgetting they're not auditioning for an Oscar.

LinkedIn has 1 billion active users as of 2024. Every second, three new people jump on the bandwagon. If it were a country, LinkedIn would be the third most populated.

But it’d definitely be the cringiest country.

There, the humblebrag has reached an art form, and self-promotion is disguised as "thought leadership." Every post feels like a carefully scripted monologue, where job titles become badges of honor and endorsements are the standing ovations everyone craves.

This disconnect between intention and execution is where we find ourselves cringing—not just at the awkwardness of the delivery, but at the blatant violation of the social codes that keep our interactions comfortable.

But exactly why do we cringe on LinkedIn? What makes us do what we do on the platform, and can we honestly stop using it? These are the kind of questions that I will attempt to answer in this blog.

1. why we cringe on LinkedIn

Let’s talk about cringe.

Cringe is that gut-wrenching feeling of secondhand embarrassment we get when we see someone trying too hard—usually to impress, but sometimes to be funny, vulnerable, or authentic in a way that just doesn’t land.

Like the class clown who keeps repeating the same unfunny jokes.

Turns out, cringe has roots on us psychologically. According to psychologist Philippe Rochat, we cringe when we see someone violate the “codes” of social interaction.

See, as human beings, we have a list of “codes” to keep things comfortable and familiar for everyone. Some rules are grounded in essential moral principles, like the prohibition against taking another person's life, while others are more trivial—guidelines that might matter to me personally but have less impact overall.

To not cringe, a LinkedIn post has to consist of one of these two things:

1) Value: Either educate or entertain people

2) Authenticity: Share genuine experiences

When someone breaks these norms—by oversharing, overbragging, or failing to read the room—we cringe because we’re hardwired to care about how others see us. It's a reminder that we, too, could mess up. It’s like seeing someone slip on ice and thinking, “Glad it wasn’t me, but also, yikes.”

Imagine an entire platform designed for professional self-promotion, where the invisible rules are constantly teetering on the edge of overstepping. That’s LinkedIn.

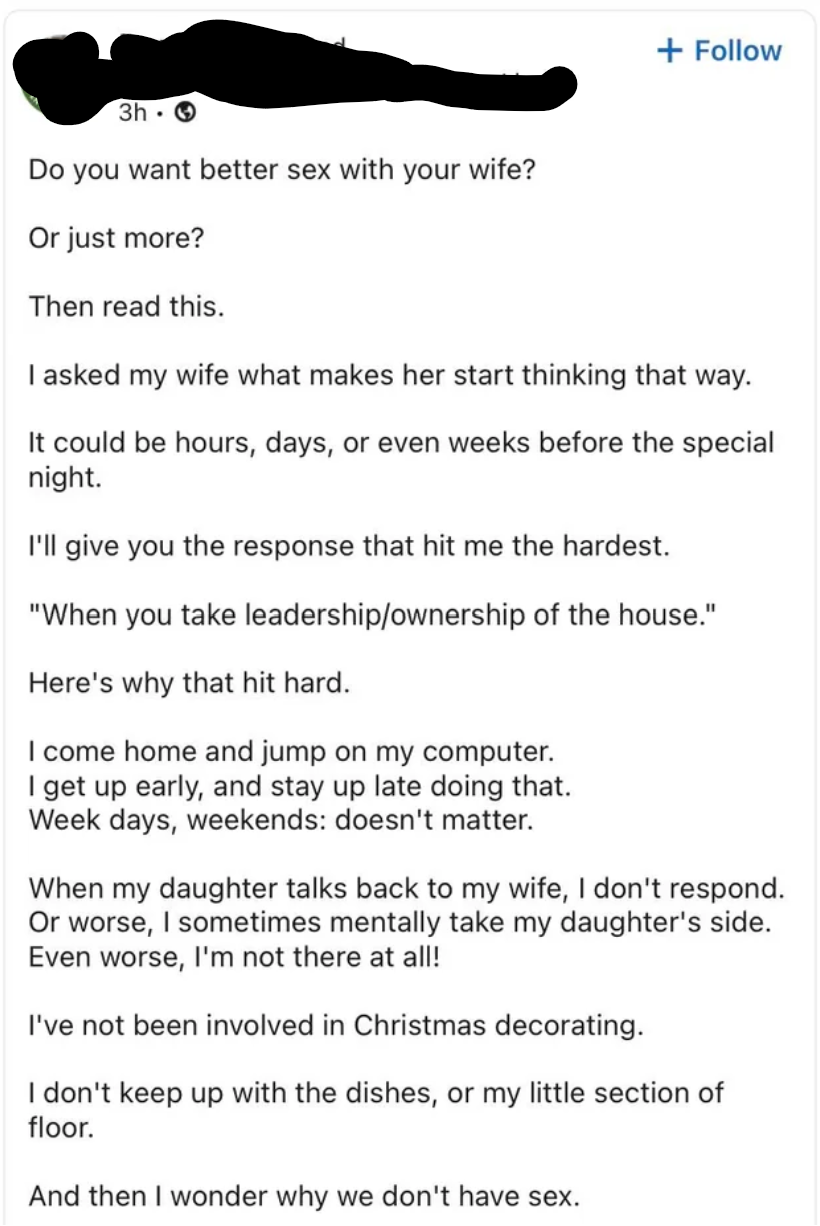

The thing with LinkedIn is that there is a 90% chance that this kind of post is trolling, but there’s a solid 10% chance that he’s serious. And sometimes you cannot tell which is which.

So, why do we do this to ourselves? Why do otherwise normal, intelligent people morph into robots programmed to spew buzzwords the moment they hit “Post” on LinkedIn?

Here’s my theory: LinkedIn is a place where everyone feels like they have to perform. It’s a stage where every act of you exists permanently, and all of your co-workers and future employers are invited. So what do we do? We turn the cringe up to 11, because we think that’s what the audience wants to see.

This creates a positive feedback cycle. You scroll LinkedIn, see someone’s cringe post racking up likes, and think, "Hmm, maybe I need to post like that." Next thing you know, you’re posting an inspirational quote about how “Leaders eat last” with a selfie of you holding a protein shake in your home office.

It’s our fault, but not entirely. LinkedIn is designed to promote this phenomenon.

2. how LinkedIn is designed for you to cringe

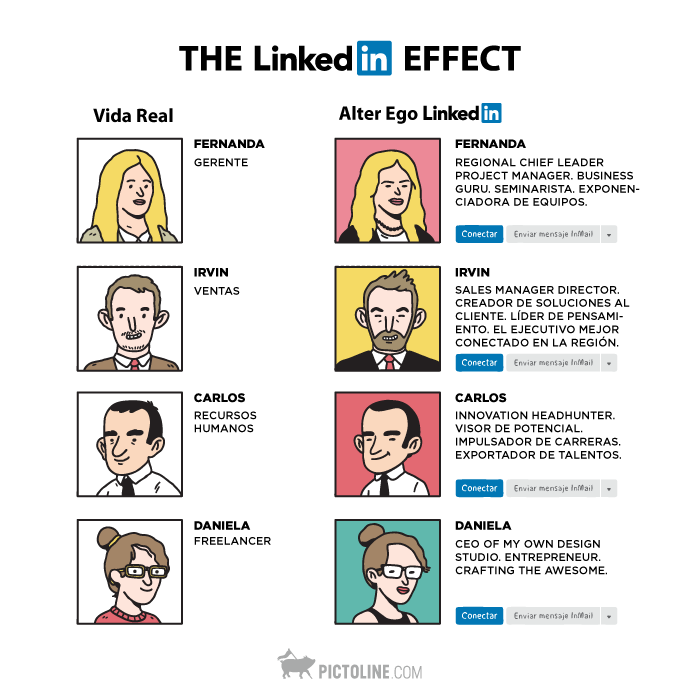

Let’s step back and think about LinkedIn for a second. Unlike Instagram or Twitter or Substack, where you can curate different versions of yourself—party self, thought-leader self, blogger self—LinkedIn demands that you show up as your most professional self. Your profile picture? Buttoned-up. Your posts? Packed with buzzwords. Your connections? People you barely know from a conference three years ago.

It’s like showing up to a party where everyone’s wearing suits, shaking hands, and talking about KPIs, but deep down you just want to chill in your pajamas. This constant pressure to perform fuels the cringe: LinkedIn forces us to sell ourselves while pretending we’re not. We all know we’re in this space to advance our careers, but we also know that blatant self-promotion feels gross. The result? LinkedIn Cringe.

Research by Goffman’s theory of self-presentation tells us that people constantly manage how they’re perceived, and authenticity always gets thrown out the window. LinkedIn magnifies this with algorithms that reward engagement, likes, and comments—leading to behavior that feels performative. And because everyone is trying so hard to be seen as "professional," even small missteps (like over-enthusiasm or forced humility) stand out in ways that feel cringe-worthy.

Platforms like Facebook and LinkedIn have pushed the art and science of ‘mass self-communication’ to a new level. Their interfaces cajole users into releasing information about themselves, both consciously and unconsciously. Users, for their part, have become increasingly skilled at playing the game of self-promotion, while advertisers and other interested parties, such as (prospective) employers, are getting leverage out of these tools for their own purposes.

The power over interfaces naturally resides with platform owners, but they constantly have to balance users’ demands with business interests—a struggle that reveals the deeper ideological and economic interest at stake in online identity formation.

At the core of this tussle we find three stakeholders: users want to build connections and preferably deploy multiple modes of self-performance aimed at different audiences; employers seek ‘true’ information about a prospective employee’s behavior and also need SNSs to monitor their employees’ online behavior; and, finally, platform owners have a vested interest in uniform narratives to maximize connectivity.

All three stakes are rooted in strategic paradoxes: each act of self-performance or personality assessment requires tactical maneuvering and awareness of the power plays involved in the game

the LinkedIn cringe loop

To survive the world of social media, you created two little characters inside your brain: Professional You and You You.

Professional You are decked out in a blazer, carrying a briefcase. They’re nervous because every single post they make could be seen by potential employers, co-workers, or industry leaders. This person spends hours crafting the perfect post, tweaking it for just the right level of humblebragging. They’re thinking: “How can I get likes and not seem desperate?”

You You, on the other hand, are wearing pajamas and lying on the couch with Cheeto dust on their hands. This person doesn’t care about buzzwords; they just want to say, “Honestly, I’m stressed about this new job, but I’m learning!” However, Authentic You rarely sees the light of day on LinkedIn because, well, Professional You keeps them locked in the basement.

What happens when Professional You win every time? The LinkedIn Cringe Loop: The more performative we are, the more engagement we get. The more engagement we get, the more we crave it. And the cringe grows.

3. the LinkedIn cringe duo

So, why does scrolling LinkedIn feel like walking through a field of rakes that all hit you in the face? Because LinkedIn has given birth to something I call The Cringe Trifecta, a perfect storm of uncomfortable behavior that only exists in the professional world.

Let’s break it down:

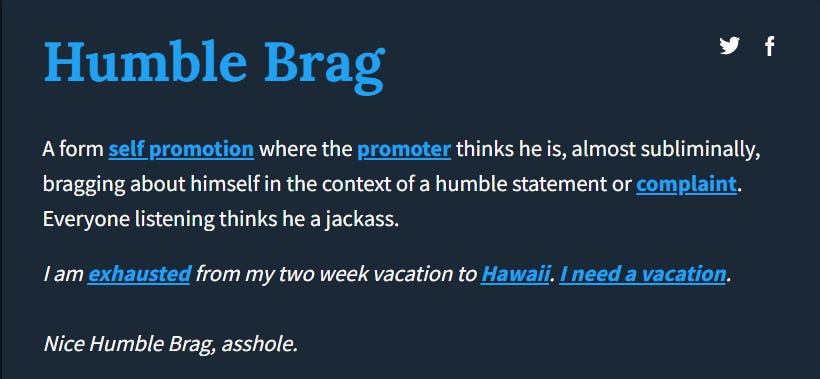

a. the humblebrag

There are many names to call these people by: humblebrag, indirect brag, brags in disguise, etc. This is basically a brag, but the author is self-aware enough to tuck it under camouflage.

The Humblebrag is like the social media equivalent of a magician not showing you the trick but expecting applause anyway. It's a performance—an attempt to sound modest while slyly slipping in some impressive feat or accolade. And trust me, it’s not just Steve from accounting who’s guilty of this. Humblebragging is practically a cultural epidemic.

Psychologists have even studied this phenomenon. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that humblebragging is actually counterproductive—it makes people like you less. In fact, researchers concluded that people who humblebrag come across as less sincere and more self-centered than if they’d just been straightforward about their accomplishments. So, not only is Steve showing off, but he's also making everyone dislike him in the process.

The brilliance of the humblebrag is in its thin veneer of humility, like the phrase “I’m so exhausted from traveling between my multiple TED talks.” You hear it and immediately know it's not about being tired—it's about how impressive it is to give TED talks. The subtlety of the brag lies in the balance: not too obvious, but just enough to make sure you catch it. If you ever catch yourself saying, “I can’t believe I’ve won *yet another* award for my groundbreaking work in something obscure but intellectual-sounding,” you’re deep in humblebrag territory.

And it’s all over LinkedIn. Take a scroll, and you’ll notice the pattern: the casual “so honored to be recognized” posts, the faux surprise at winning an award, or the classic “I’m truly humbled to have led this successful merger of two Fortune 500 companies.” Truly humbled? Probably not.

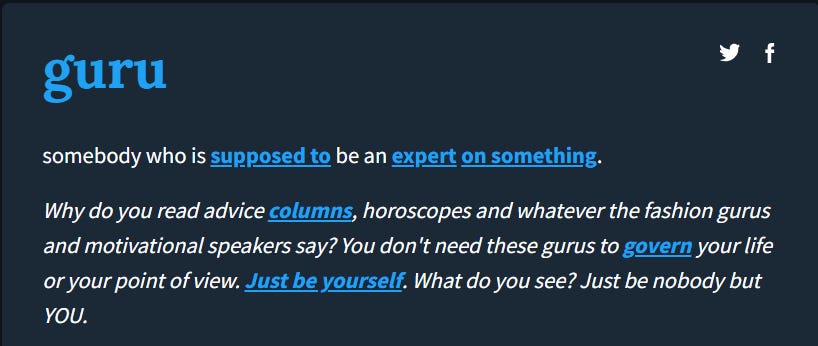

b. the guru

Ah, the LinkedIn TED Talk Syndrome—where every post looks like something a person would write from memory after a glance at Tony Robbins’s notes. This is where LinkedIn users transform into self-proclaimed life coaches, delivering profound insights that are about as deep as a kiddie pool.

The formula is as predictable as it is cringeworthy. First, you start with a #hustle or #grind metaphor that makes you wonder if the poster has ever actually been on a mountain, or if they’re just reading motivational books on a beach somewhere. “Life is like climbing a mountain…” they begin, as if scaling Everest is the only way to understand their deeply profound thoughts about quarterly earnings.

Next, they drop a platitude so vague that it’s practically a cosmic riddle. “Success is what happens when you stop waiting for the elevator and start taking the stairs.” Ah, yes. Because, clearly, the key to corporate success is not about strategy or hard work but simply about choosing the staircase over the elevator, or maybe just hitting the gym a bit more often. It’s like saying, “Happiness is found in the journey, not the destination,” but without the commitment to actually defining either of those terms.

The pièce de résistance is the awkward selfie, usually taken in a poorly lit room with a backdrop that screams, “I just rolled out of bed.” The selfie is coupled with a promise to keep grinding, an obligatory call-out to the LinkedIn community: “Keep pushing forward, LinkedIn fam. #MotivationMonday #Leadership #NoDaysOff.” It’s as if the selfie is supposed to be the visual equivalent of a motivational speech, inspiring hundreds of likes for reasons known only to the algorithms of LinkedIn’s engagement metrics.

So why do these posts get so many likes? It’s a mystery, much like why anyone would willingly watch a TED Talk on how to tie knots. But here’s the secret: it’s not about the content. It’s about the performative hustle and the visual proof that the poster is, in fact, climbing that metaphorical mountain while we’re all here, waiting for the elevator. The result? An endless loop of likes, engagement, and the occasional eye roll.

4. why do people act cringe on LinkedIn?

People act this way on LinkedIn because of a potent mix of social media dynamics, professional pressure, and psychological tendencies. Research into social behaviors on social media platforms like LinkedIn provides insights into why users feel compelled to post in ways that are, frankly, cringe-inducing.

a public stage

At its core, LinkedIn is a professional network, but it has increasingly become a public stage where people feel the need to perform success. This performance pressure stems from a combination of impression management and the "fear of missing out" (FOMO), which is amplified in career-focused environments.

According to a 2018 study published in the Journal of Business and Psychology, people actively curate their online personas to influence how others perceive them. On LinkedIn, this translates into posts that highlight achievements, sometimes excessively, in order to boost one’s professional reputation .

But why the humblebrag? Social scientists have long studied this phenomenon. The term, coined by comedian Harris Wittels, refers to a brag disguised in self-deprecation or modesty, and it's all over LinkedIn. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that humblebragging is counterproductive; it makes people like you less.

According to the research, people who humblebrag come across as less sincere and more self-centered than those who are straightforward about their accomplishments . This means Steve from accounting isn’t just showing off his “surprise” award—he’s also shooting himself in the foot socially. The humblebrag’s subtle bragging wrapped in false humility isn’t fooling anyone, but LinkedIn encourages it because users believe it paints them as both accomplished and modest.

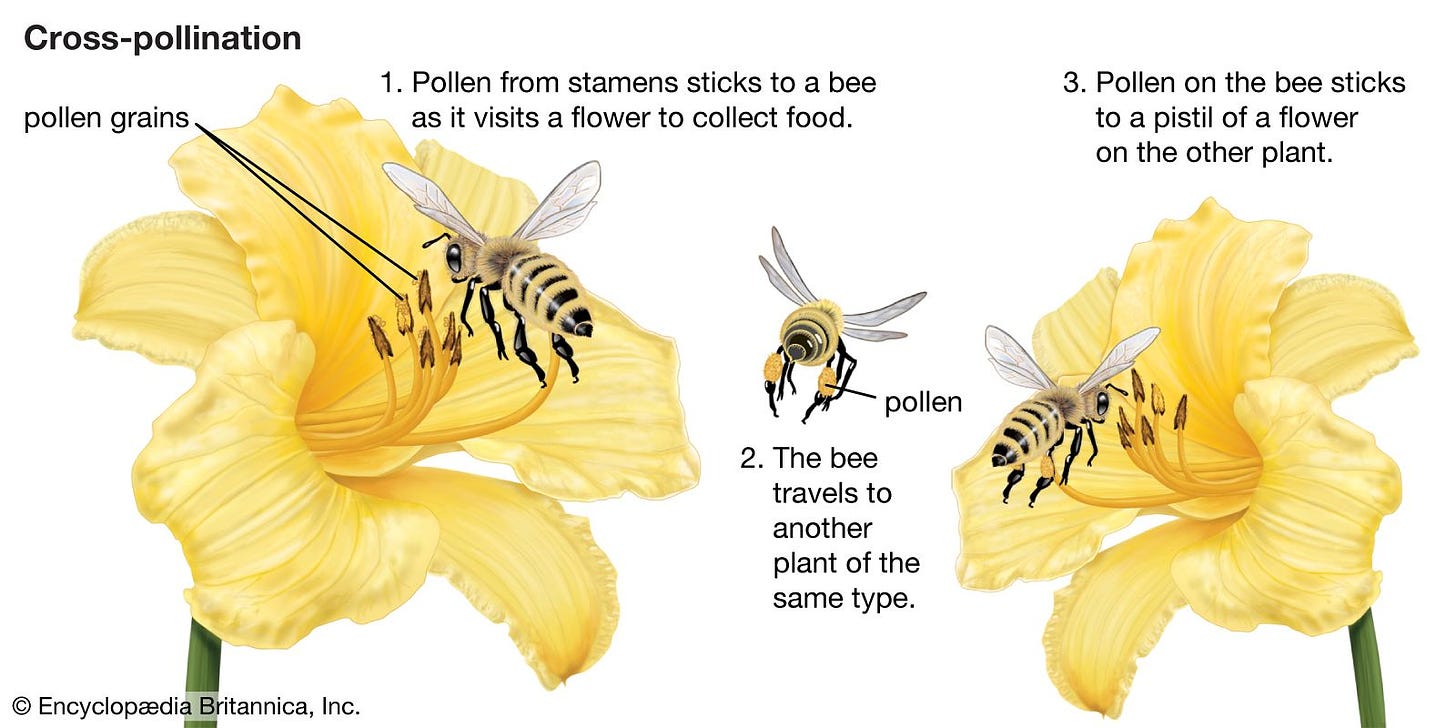

cross-pollination effect

The cross-pollination effect refers to how behaviors and trends from one social media platform influence and migrate to others, particularly as users adapt familiar habits from more personal platforms like Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter into a professional context like LinkedIn.

LinkedIn didn’t evolve in isolation. As platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter became central to personal branding, the habits people developed on those networks naturally bled into LinkedIn. Self-promotion, once limited to sales pitches or annual performance reviews, has become a daily activity, with people packaging their achievements and life lessons for their professional network.

The rise of the motivational guru is a prime example of this. A 2020 study in Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace analyzed the rise of pseudo-inspirational content on professional platforms like LinkedIn, identifying it as an extension of Instagram's “influencer culture.”

The formula is simple: post a vaguely profound insight, wrap it in metaphors, throw in a couple of hashtags, and voila—you’re now a thought leader.

This approach isn’t about sharing deep insights; it’s about crafting content that’s bite-sized, easily shareable, and designed to get likes.

These posts get engagement not because they’re insightful, but because they signal to others that the poster is part of the “hustle” culture. It’s performative—people aren’t writing these posts because they’ve cracked the secret to success, but because they want to be seen as someone who has.

feeding the algorithm beast

Let’s not forget the algorithm.

LinkedIn’s algorithm is horny for posts with higher engagement by pushing them to more users, which incentivizes people to post what will get likes, shares, and comments. A 2022 study in Computers in Human Behavior looked into LinkedIn’s algorithmic impact and found that posts with emotional appeal, particularly motivational content, were more likely to be promoted by the platform. This is why we see the same formula over and over again: a humblebrag post, a motivational speech, or some corporate jargon dressed up as life advice. The algorithm doesn’t care about depth or originality; it only cares about engagement. Because engagement, again, invites ads.

This creates a feedback loop: the more likes and comments a post gets, the more it’s seen, and the more people are likely to emulate that content, thinking it’s the key to success on the platform. Thus, we get a flood of "Keep grinding!" posts and humblebrags about winning "yet another" award.

The customer demand is so great, and the tone is so uniquely LinkedIn, there is even an AI made specifically just to parody these types of posts. And the Internet, being moronic as it is, had a fuck field day.

insecurity and social comparison

Underlying all of this is insecurity.

Social comparison theory, developed by psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s, explains how people determine their own social and personal worth based on how they stack up against others. LinkedIn, with its professional focus, is fertile ground for this kind of comparison. A study published in Psychology of Popular Media Culture in 2019 explored how LinkedIn fosters a comparison trap, where users feel the need to project an image of perpetual success.

People post their accomplishments not just to celebrate them, but to reassure themselves—and others—that they’re doing well in their careers.

This is why so many LinkedIn posts feel less like genuine updates and more like performances. People aren’t just sharing for the sake of it—they’re crafting a narrative, ensuring they’re seen as valuable, successful, and constantly climbing that metaphorical mountain. It’s not enough to be successful; on LinkedIn, you have to look successful, too.

5. why are we still on LinkedIn?

LinkedIn: the platform that’s as unavoidable as a work meeting and as awkward as making small talk at a networking event. We’ve all had that moment where we thought, "Why am I even still here?" You know, when you’re 45 minutes into a scroll, and the last thing you saw was a post about someone’s third consecutive promotion, followed by a #MotivationMonday quote that left you questioning your entire career path. Yet, here we are, still logging in, still scrolling. Why?

To answer that, we need to dive into the strange psychology and mechanics of LinkedIn. Let’s break this down.

a. LinkedIn is a necessary evil (because, yes, networking)

First off, we can’t ignore the obvious reason: LinkedIn is a professional necessity. You know it, I know it. The platform was literally built for you to look good in front of future employers and professional connections. In a world where jobs come and go faster than you can swipe left on a bad Tinder match, LinkedIn offers a sense of security. You don’t want to miss out on potential opportunities, so you log in, even if it’s just to make sure your profile picture still screams, "I’m hireable!"

The networking power of LinkedIn is no joke. Studies show that 85% of jobs are filled through networking, and LinkedIn is responsible for nearly 77% of all job placements online. If you’re not on LinkedIn, you’re essentially missing out on three-quarters of the job market. Because who even hires offline now?

So yeah, we’re here because, at least for now, we have to be. LinkedIn, in a sense, put food on our and our cat’s plates.

b. LinkedIn knows how to hook you

Let’s get real for a second. LinkedIn is social media, even if it wears a suit and tie. And like all social media platforms, it taps into a deeply human need: validation. The moment you post a new job update or share a humblebrag about your latest side hustle, the dopamine rush begins. The likes, comments, and congratulations start pouring in, and suddenly you’re feeling pretty good about yourself.

That fleeting moment where your professional ego gets inflated by all the likes from people you haven’t talked to since high school. It's a quick hit of self-worth that keeps you coming back for more. After all, why do we post anything online if not to feel noticed?

According to behavioral scientist BJ Fogg, social media platforms (yes, even LinkedIn) are designed to create habit loops. The feedback loops (likes, comments) on LinkedIn trigger a reward system in your brain, making you associate logging in with positive reinforcement.

This is why LinkedIn’s feed feels like a professional slot machine—you keep pulling the lever, hoping to win some validation.

c. the fear of falling behind

Now, here’s the existential one: FOMO—the Fear of Missing Out. On LinkedIn, it’s not just about missing a party; it’s about missing the entire career ladder. Every time you log in, you’re confronted with posts about other people’s successes. Promotions, new job titles, certifications, international speaking gigs—LinkedIn becomes a feed of “Here’s why you’re falling behind,” and that taps into one of the deepest anxieties we all have: Are we doing enough?

Once you fall into it, it’s hard to escape. You start off just checking notifications and end up spiraling into a black hole of someone else’s career achievements. Why? Because LinkedIn, like all social platforms, is driven by comparison.

Psychologists have studied something called social comparison theory, which explains that humans evaluate themselves based on comparisons to others. Like a monkey feels ugly only if it has one less boyfriend than that oragutan the next cage. And on Linkedin, we are all monkey. These comparisons are especially painful because they revolve around career status—a core part of our identity. Seeing someone else succeed triggers feelings of inadequacy, pushing us to log in more often to stay competitive.

d. the illusion of opportunity

Let’s talk about the carrot at the end of the stick. LinkedIn sells the idea that at any moment, a game-changing opportunity could drop into your inbox—a dream job offer, a lucrative freelance gig, a high-profile connection. So, you stick around because, what if? What if that recruiter DM’s you tomorrow with the chance of a lifetime? What if your next post goes viral, and suddenly you’re a thought leader in your industry? Someone’s gotta win, right?

LinkedIn capitalizes on what psychologists call intermittent reinforcement—the same mechanism that makes gambling addictive. Sometimes you’ll get a message from a recruiter or a post that gets tons of engagement, and that’s enough to keep you logging in, day after day, even if most of the time you’re just seeing fluff posts.

e. we all want to look good

Finally, let’s not forget the image factor. LinkedIn is where you perform your professional self. It’s like a never-ending job interview where you have to look polished, competent, and successful. That’s exhausting, but it’s also incredibly hard to walk away from. No one wants to be the person who quits the only platform where your career might get noticed.

The more time you spend on LinkedIn, the more you feel like you have to maintain the perfect version of yourself. And the higher the stakes get, the more invested you become in sticking around.

Studies have found that people tend to create “idealized” versions of themselves on social media platforms, including LinkedIn. According to Erving Goffman’s theory of impression management, LinkedIn isn’t just a tool for networking—it’s a place where you craft your professional identity, carefully curating what others see.

This makes LinkedIn less about connection and more about performance, and once you’ve built your persona, it’s tough to walk away.

In the end, we’re still on LinkedIn because it’s like a weirdly addictive cocktail of career necessity, validation, comparison, and opportunity. It’s the professional space where we feel like we have to be, even if it makes us cringe sometimes. And like any performance, LinkedIn requires an audience, so as long as everyone else is there, we’ll probably keep showing up too.

Until, of course, someone creates a better version.

And when they do? I’ll be the first to announce it on LinkedIn.

#Blessed #ExcitedToShare #NeverStopLearning

Em phải đọc 3 4 lần gì mới xong được bài này của anh =))) maybe do dù em chưa relate lắm với LinkedIn nhưng em cũng "nghe tiếng" về sự cringe của nó rồi. Bài post đầu tiên (và duy nhất tới bây giờ) của em trên LinkedIn là 2 câu, AI-generated (em nhét cho AI sự cringe thay vì tự em cringe lol)

Anw phần em thích nhất trong bài là "the illusion of opportunity", vì em thấy mn hay chia sẻ những tips kiểu những cơ hội việc làm/connections bất ngờ đến từ LinkedIn, và có vẻ trên LinkedIn có quá nhiều (?) người tuyệt vời và giỏi giang đến nỗi mình không nỡ bỏ qua cơ hội dù chỉ là 0.0001% được connect với họ.