how to gaslight, gatekeep, and girlboss your way through any online debate

the ultimate guide to arguing online

What do you need when arguing online?

Logic?

Reason?

A rock-solid grasp of the facts?

Yeah, no.

See, I used to think that if you came armed with airtight arguments and a well-researched arsenal of evidence, you’d automatically win. That people would read your points, have a little moment of self-reflection, and say, “Duy, I was completely wrong, cheers for setting me straight.”

Turns out, that basically never happens. Instead, you just get quoted by someone with an anime profile picture calling you “brain-rotted”.

This was a hard lesson for me, mostly because, according to my now-ex, I’m already insufferable to argue with in real life. Apparently, approaching disagreements with logic and solutions instead of emotions is not a particularly lovable trait in a boyfriend. Who knew?

But when I took this same approach online—specifically, on Threads, where people go to shout their opinions into the void—I quickly realized that even airtight reasoning won’t get you very far. If anything, it just makes people angrier.

Some of my debates were interesting. Most felt like slamming my own head against a brick wall and then getting yelled at for bleeding on it. I legitimately had one person so delusional they asked me to apologize to them on my page if they won the argument.

Clearly, I needed a new strategy. A philosophy. A way to navigate the digital battlefield of bad takes and reactionary nonsense without losing my mind.

So, in an attempt to both preserve my sanity and satisfy my deep, primal urge to correct strangers on the internet, I’ve decided to take a step back and set up some actual ground rules for myself.

But first,

1. why argue online?

Before we get into what you should do arguing online, we should talk about why we argue online in the first place. Before we get into why people argue online, let’s talk about what should not be the reason you argue online.

If you were to forget almost everything I said in this post, this is what I think is important for you to remember:

Debates are meant to convince a third party, not the person you're debating.

Debates are not a great way for two people to come to an understanding. When you put pressure on someone's views they're way more likely to double down than to reconsider. A better alternative is to ask nonprovocative questions from a place of genuine curiosity. And just listen.

Their logic will be tested as they explain, and they'll probably be the first to realize if something doesn't add up.

But debate and argument? Hardly a good way for someone to change their mind.

So what should you argue for?

a. for engagement

People argue online because the internet is a massive, poorly supervised daycare where every toddler has just discovered that yelling louder might get them the last cookie.

Social media platforms thrive on engagement, and few things engage people more than heated debates. A 2021 study published in Science Advances by researchers at Yale University1 found that social media platforms amplify expressions of moral outrage over time.

This figure shows how the political extremity of a person’s online social network affects their likelihood of expressing outrage in tweets. The first graph (A) compares two groups: users discussing the Brett Kavanaugh nomination (blue) and those engaging with a more neutral “United” topic (orange). It reveals that Kavanaugh users are more likely to be part of ideologically extreme networks, while United users tend to have more moderate networks.

The second graph (B) shows that as a person’s network becomes more politically extreme, their likelihood of expressing outrage increases. This trend is stronger for Kavanaugh users, meaning people in highly polarized discussions are more likely to tweet with outrage, reinforcing the idea that echo chambers fuel emotional reactions.

This amplification occurs because users learn that such expressions are rewarded with increased "likes" and "shares" on platforms like Twitter and Facebook. The study demonstrated that social feedback, such as likes and shares, significantly predicts future moral outrage expressions, indicating that reinforcement learning shapes users' online behavior.

This phenomenon is further amplified by the online disinhibition effect, which suggests that anonymity and lack of immediate social consequences make people more aggressive online.2

Writing that very last part makes me remember Marina Abramović’s performance "Rhythm 0."

In the piece, Abramović placed herself completely at the mercy of the audience, allowing them to use various objects on her without any intervention.

Just as the online environment strips away responsibility and emboldens extreme actions, "Rhythm 0" demonstrated how the absence of accountability can lead individuals to push boundaries and, at times, inflict harm.

Social media also creates ideological echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs.3 Algorithms naturally push users toward content they already agree with, deepening polarization. Exposure to opposing political viewpoints can even make users more entrenched in their original views, rather than opening them up to new perspectives. 4

In summary, the internet not only hosts arguments but actively cultivates and rewards them, often without changing users' minds.

b. for your own enjoyment

Social media platforms have become integral to modern identity formation, particularly in a context where traditional community ties are dissolving. Engaging in online debates often serves as a means to fulfill needs for identity and belonging, as individuals align themselves with specific groups or causes. This behavior is particularly evident when defending one's "in-group," whether that be a fandom, political ideology, or niche internet subculture.

This phenomenon aligns with Social Identity Theory (SIT), proposed by Tajfel and Turner (1979)5, which posits that individuals derive a sense of self-worth from their group affiliations. SIT explains why people defend their in-groups aggressively, especially in online environments where anonymity can amplify these behaviors.6

Online communities provide a space for individuals to express and reinforce their identities through shared values and beliefs, often leading to in-group favoritism and out-group negativity.

Online debates frequently function as ideological theater, where the primary goal is to perform for an audience that already agrees with you rather than to convince the opposing side.

Individuals engage in these debates to gain social approval from their in-group, often measured in likes, shares, and retweets. This behavior is consistent with broader research on how social media platforms facilitate group dynamics and reinforce existing beliefs7.

Online communities offer a unique space for identity exploration and formation. For instance, online fandom communities allow individuals to engage in self-expression and form meaningful connections with others who share similar passions8. The dynamic nature of these communities enables individuals to navigate complex processes of identity formation and belonging.

Additionally, social media platforms influence behavior by creating norms that individuals feel compelled to follow. This is evident in how users align their actions and opinions with those of their in-group, even if it means adopting behaviors or views that they might not hold offline.

Online communities can be particularly important for marginalized groups, offering spaces for identity exploration and acceptance that may not be available offline. This underscores the role of social media in facilitating diverse forms of identity expression and community building.

While online debates can lead to conflict, they also provide opportunities for deeper discussions and community bonding. The resolution of conflicts within online communities can strengthen group ties and reinforce collective identity.

c. for the sake of holding people accountable

The internet gives everyone a megaphone, which means bad takes don’t just die in private—they spread, multiply, and occasionally end up on a TED Talk stage.

Sometimes, engaging in arguments isn’t just about entertainment; it’s about pushing back against misinformation, lazy thinking, and whatever new pseudo-scientific nonsense is trending that week. Sure, you won’t always change minds, but at the very least, you can make sure bad ideas don’t go unchallenged.

So essentially, online arguments persist because of a cocktail of psychological vulnerabilities, technological manipulation, and a desperate craving for validation. It’s the digital equivalent of people who shout at pigeons in the park, convinced they're making a difference—except the pigeons now have Wi-Fi.

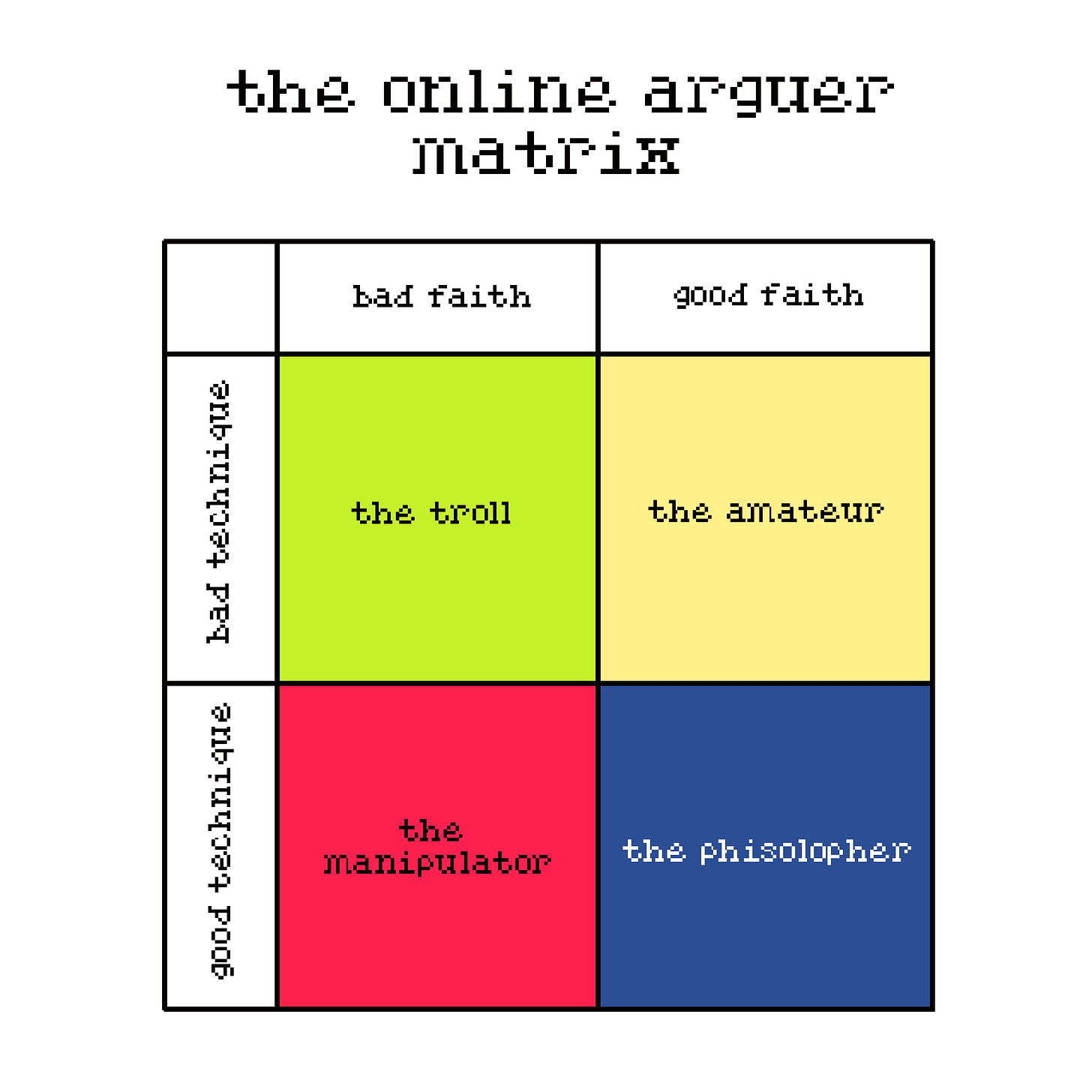

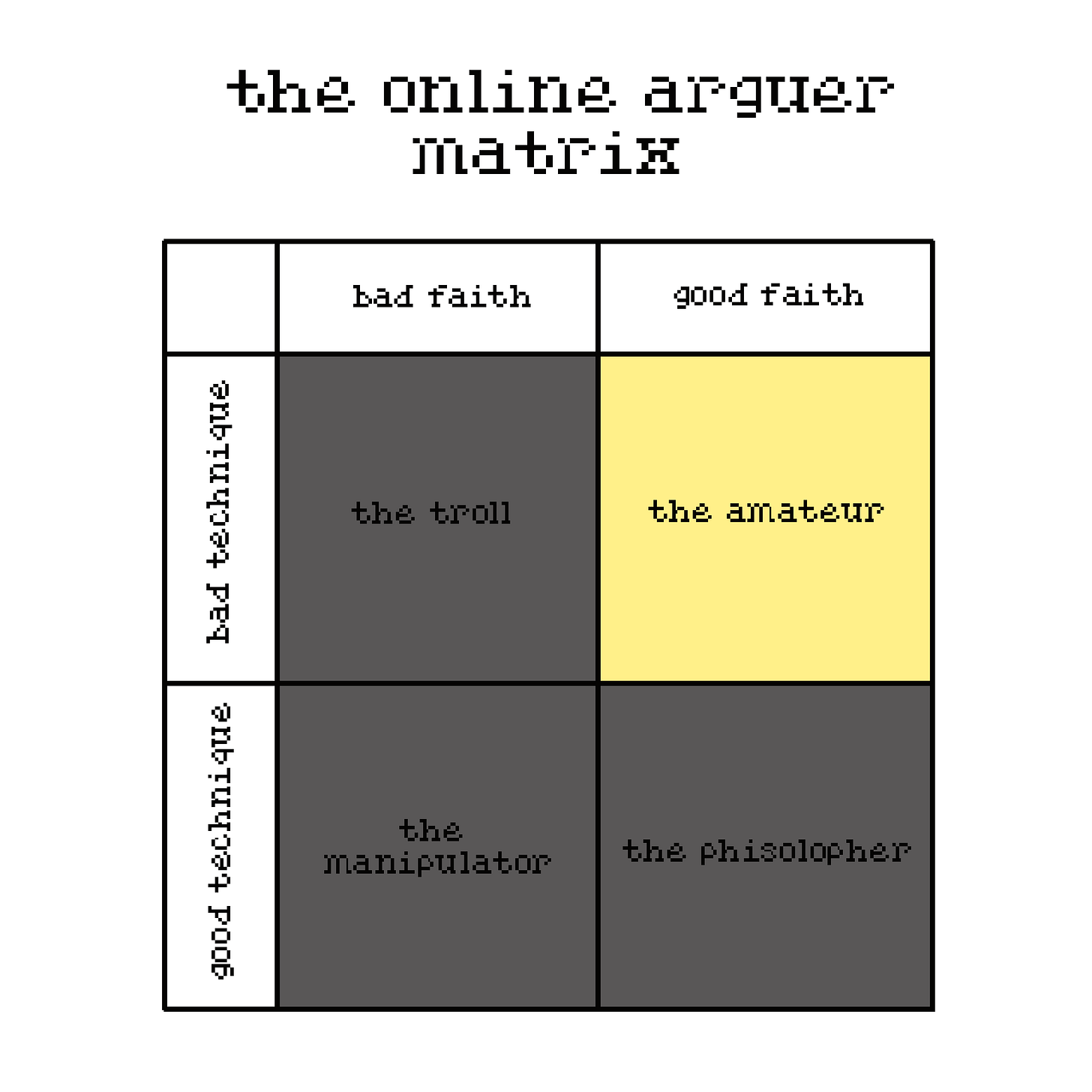

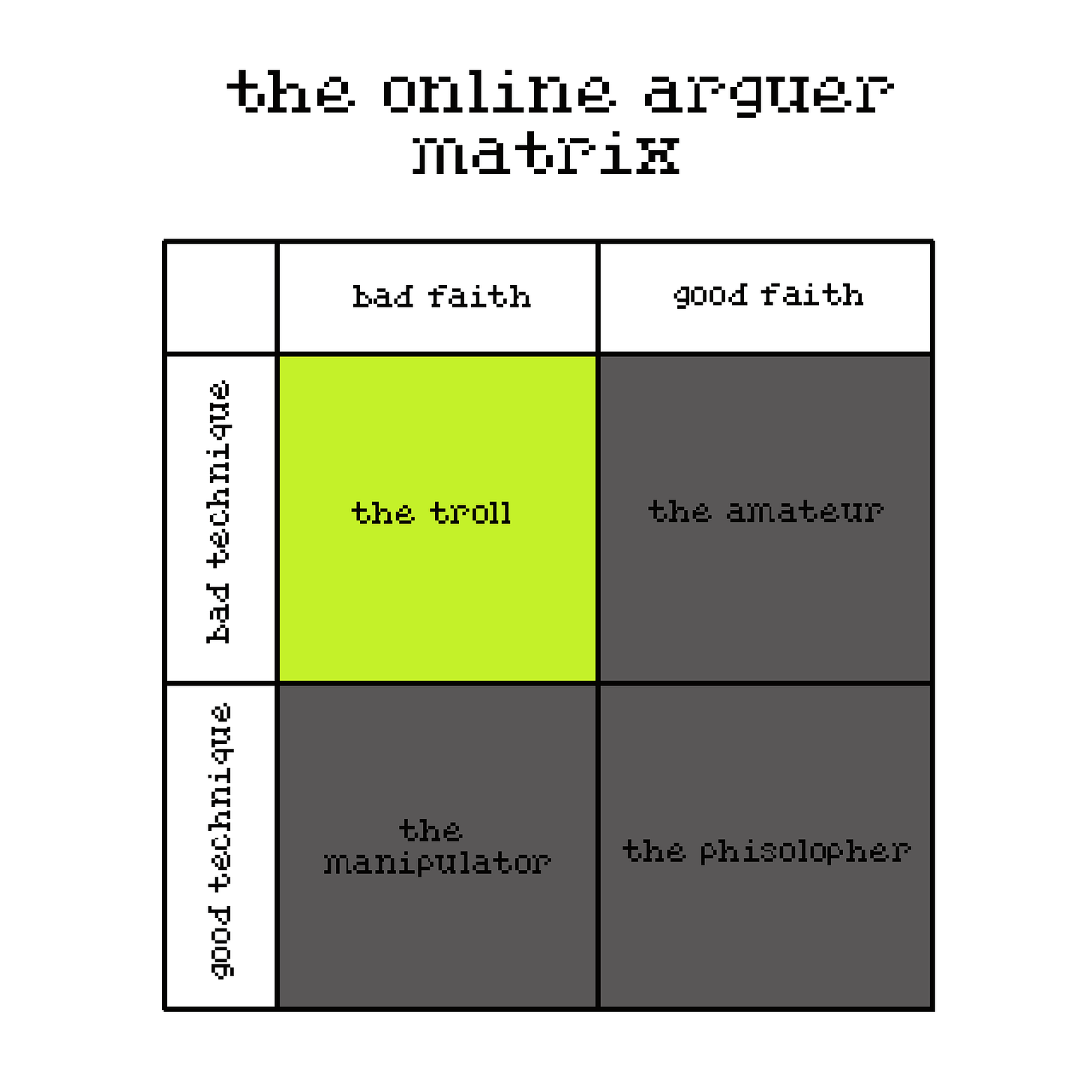

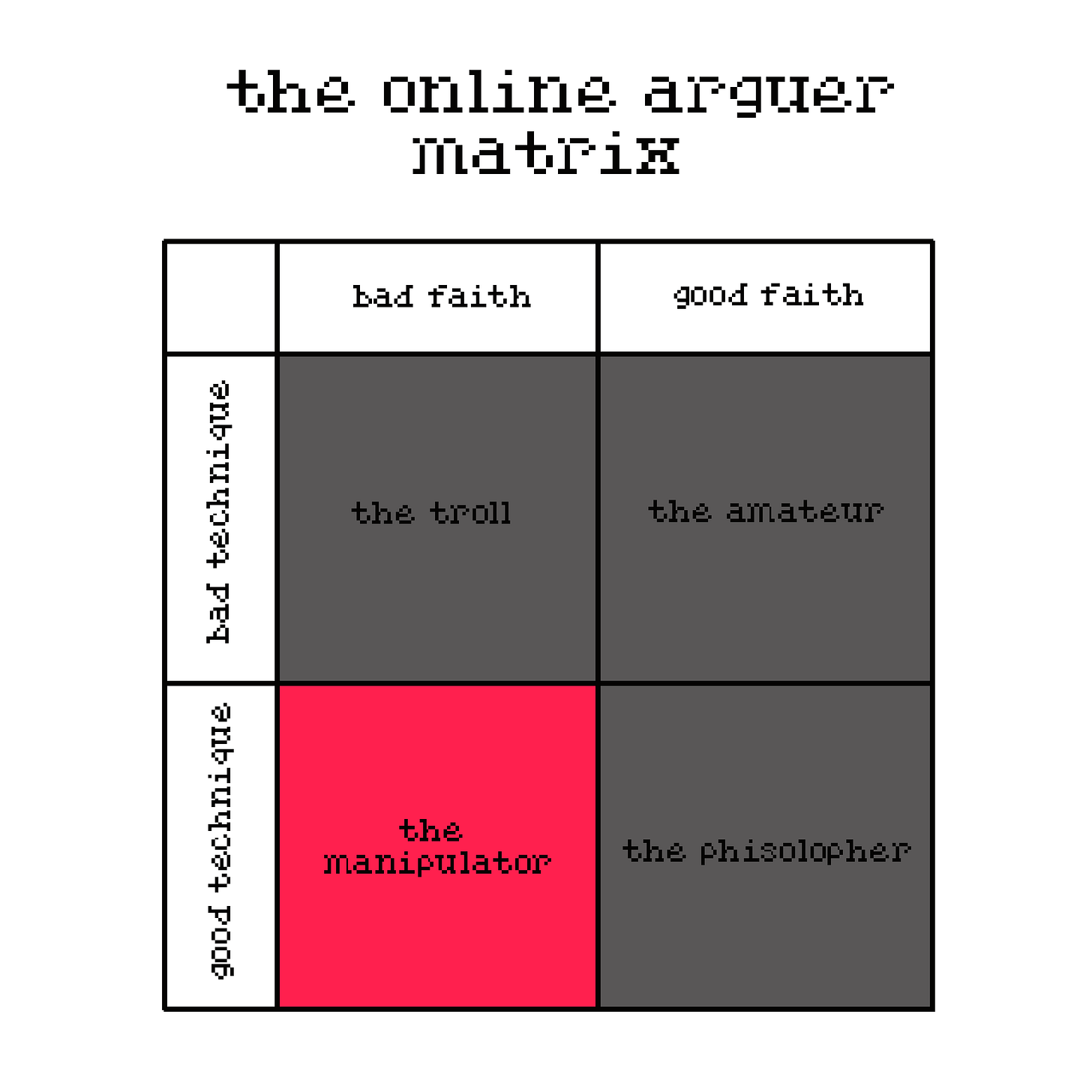

2. the online arguer matrix

The Online Arguer Matrix is something I made what happens when you take every excruciating internet debate you've ever seen and sort its participants into four neat little boxes.

It’s a simple two-axis system: one measures how well someone argues—ranging from clumsy, logic-mangling messes to razor-sharp rhetorical mastery. The other measures why they argue—whether they genuinely seek the truth or just want to stir chaos.

This leaves us with four types of arguers:

The Philosopher – Actually knows what they’re doing and argues in good faith. A rare species.

The Amateur – Well-meaning but incompetent, like a toddler wielding a plastic sword.

The Troll – The conversational equivalent of a raccoon knocking over trash cans.

The Manipulator – Just as skilled as the Philosopher, but with a villainous mustache.

Each of these characters plays a role in the theater of online discourse. And if you’re wondering which one you are—well, buckle up. It’s time to take a closer look.

a. the Philosopher—good faith, good technique

The Philosopher seems like a normal internet arguer, but they’re actually an anomaly—a rare species in the wild, someone who debates in good faith. By engaging in discussions with actual curiosity, they seem like just another opinionated person—but they never seem to get caught in the usual online shouting matches.

Philosophers have clever brains, and good faith is the brain’s most clever trick. The brain knows that the Average Internet Debater, who can be reactionary, can be appeased if it just slings enough arguments back and forth. So the Philosopher’s brain creates a battle that looks like a normal argument but isn’t—because instead of fighting to win, the Philosopher fights to understand.

It relies on one major delusion of the Average Internet Debater—that arguing = thinking.

So an Average Debater will spend the whole day composing Twitter replies, making hot takes, debating in comment sections, crafting devastating clapbacks, and if they’re judging themselves by time spent “engaging with ideas,” they’re a smashing success.

But at the end of the day, the satisfaction they feel has a hint of emptiness to it, and the thrill of arguing never quite turns into the thrill of learning. They may have convinced themselves that they’re refining their thoughts, but in their subconscious, they know they’re mostly reinforcing the ones they already had. Their feelings of intellectual rigor come along with an undercurrent of stagnation.

In reality, they’re living in a grand, overarching illusion, brilliantly crafted by their own confirmation bias. Rather than try to seek truth, the Average Debater’s brain tricks them into fighting the wrong battle—defending their position rather than examining it. And they win that battle, again and again, which leads them to believe they’re doing a good job.

the philosopher’s secret weapon

Instead of treating every argument like a war zone, the Philosopher does something radical: they try to understand what’s actually being said before responding.

They ask real, useful questions—not to trap you, but to make sure they get your point.

They don’t assume you’re an idiot (unless you are, in which case, they’ll still be polite about it).

They’re here to refine their own thinking, not just dismantle yours.

This means arguing with a Philosopher is weirdly… pleasant? Even when they disagree, they’re not hostile. They just lay out their reasoning, listen to yours, and—brace yourself—sometimes even change their mind.

b. the Amateur—good faith & bad technique

The Amateur might seem like a decent conversation partner—like that friendly guy at a party who always smiles and nods. But really, they're a walking disaster—a well-meaning debater with the technique of a soggy piece of toast. They engage with genuine curiosity, making it look like they’re on the right track, yet actual progress in debates always slips through their fingers.

Amateurs have eager minds, and eagerness is the mind’s sneakiest con artist. Their brain convinces them that since the Average Internet Debater thrives on bad faith and flimsy arguments, sincerity alone is the perfect antidote. So, they meander through discussions, hoping something useful will emerge by accident.

This all boils down to one critical delusion: the Amateur believes being open-minded is the same as being persuasive.

So, what do they do? They absorb every viewpoint, toss out unstructured counterpoints, agree too quickly, backtrack, over-explain, and apologize for things that don’t need apologizing. If success were measured by niceness, they’d be champions. But every debate leaves them with a nagging emptiness—like eating a full meal yet still feeling hungry. They might think they’re being reasonable, but deep down, they know they’re getting steamrolled.

Instead of sharpening their arguments, they convince themselves that engaging in good faith is enough. And so they keep at it, mistaking motion for progress.

the Amateur’s fatal flaws

Rather than treating arguments as battles, the Amateur aims to keep things civil. It backfires.

They assume good faith—even when they shouldn’t. They ask broad, unfocused questions that barely challenge anything. They hedge every statement until their point is barely a whisper. They’re here to learn, but they never land anywhere.

And that’s why debating an Amateur is maddening. Even when they make a solid point, it’s so soft and tentative that it feels weightless. They gesture at ideas, let them hang, and then retreat into uncertainty the moment they’re challenged.

At the core, the Amateur’s biggest flaw isn’t just being too nice—it’s mistaking endless dialogue for actual persuasion.

c. the Troll—bad faith & bad technique

What’s even worse than the Amateur? Someone who doesn’t even have good faith.

They’re a walking catastrophe—a bad-faith debater with zero technique and even less self-awareness. By launching themselves into every argument with maximum aggression, they seem engaged. They are engaged. But the only thing they ever accomplish is making everyone involved regret logging on.

Trolls have chaotic brains, and chaos is the brain’s most destructive trick. The brain knows that the Average Internet User—who just wants a normal discussion—can be dragged into a pointless brawl if provoked correctly.

So the Troll’s brain sets up a battle that swings back and forth between misdirection and nonsense. And the beauty of this move? The Troll thrives in pure, meaningless conflict. It’s built on one central delusion—that winning = making the other person mad.

So a Troll will spend the whole day posting inflammatory nonsense, dodging direct questions, shifting goalposts, spamming memes, and misrepresenting arguments. And if they’re judging themselves by how many people they’ve pissed off, they’re a smashing success.

But when the screen goes dark, the satisfaction feels hollow. The “wins” don’t feel like wins. They may have convinced themselves they’re dominating the debate, but somewhere in their subconscious, they know they’re mostly just making noise. Their feelings of superiority come packaged with an undercurrent of irrelevance.

In reality, they’re living inside a grand, overarching failure, brilliantly crafted by their own need for attention. Rather than construct a coherent argument, the Troll’s brain tricks them into thinking that causing chaos is a form of success. And because the internet has an infinite supply of new victims, the cycle never ends. They do it again. And again. And again. Until they start believing they’re some kind of rhetorical genius.

the Troll’s playbook

The Troll doesn’t treat debate as a chance to engage. They do something much dumber: they treat it like a game where the only goal is to annoy people.

They don’t try to win arguments—they try to exhaust their opponent.

They derail discussions with the subtlety of a wrecking ball.

They make statements they know aren’t true, just to see who reacts.

They are never, ever arguing in good faith.

This means arguing with a Troll is pointless. Even when you demolish their argument, they’ll just move on to another bad one, pretending the first never happened. They’ll never admit they’re wrong. They’ll never learn anything. They’re just here to waste your time.

d. the Manipulator—bad faith & good technique

The last and absolute worst: The Manipulator.

The Manipulator doesn’t argue to find the truth. They argue to win. And they’re good at it. Really good.

Manipulators have razor-sharp minds, and sharpness is the mind’s most dangerous trick. The mind knows that the Average Internet User—who just wants an honest discussion—can be overwhelmed by someone who debates with the precision of a trial lawyer. So the Manipulator’s mind sets up a battle that swings between surface-level reasonableness and deep-seated deception. And the beauty of this move? The Manipulator doesn’t care if they’re right—as long as they seem right.

But winning isn’t enough. The Manipulator doesn’t just want to beat you—they want you to feel beaten. They want you flustered, exhausted, questioning your own sanity. If you walk away from the conversation frustrated, drained, and doubting yourself, they consider that an even bigger victory.

So a Manipulator will spend the whole day constructing airtight arguments with a hidden agenda, using rhetorical sleight of hand, cherry-picking evidence, playing semantics games, and subtly shifting the goalposts. And if they’re judging themselves by how many people they’ve outmaneuvered and annoyed, they’re a smashing success.

But when the debate ends, the victory feels… off. Hollow. Their “wins” don’t feel like wins. They may have convinced themselves they’re an intellectual powerhouse, but somewhere in their subconscious, they know they’re mostly just playing a game.

the Manipulator’s playbook

A normal person enters a debate expecting a mutual search for understanding. The Manipulator does something else entirely: they turn it into a courtroom where they’re both the lawyer and the judge.

They never argue in good faith—but they make sure you do.

They don’t debate to learn—they debate to trap you.

They use real, well-structured logic—but only the parts that help their case.

They’ll misrepresent your argument—but so subtly you won’t notice until it’s too late.

They’ll force you to defend a position you never took—just so they can crush it.

They don’t just want to win—they want to frustrate you until you break.

Which makes arguing with a Manipulator disorienting. Even when they’re wrong, they sound right. Even when you catch them twisting your words, they never admit it. They’ll use every intellectual trick in the book—misdirection, false equivalence, selective quoting, feigned ignorance—until you’re not even sure what you were arguing about in the first place.

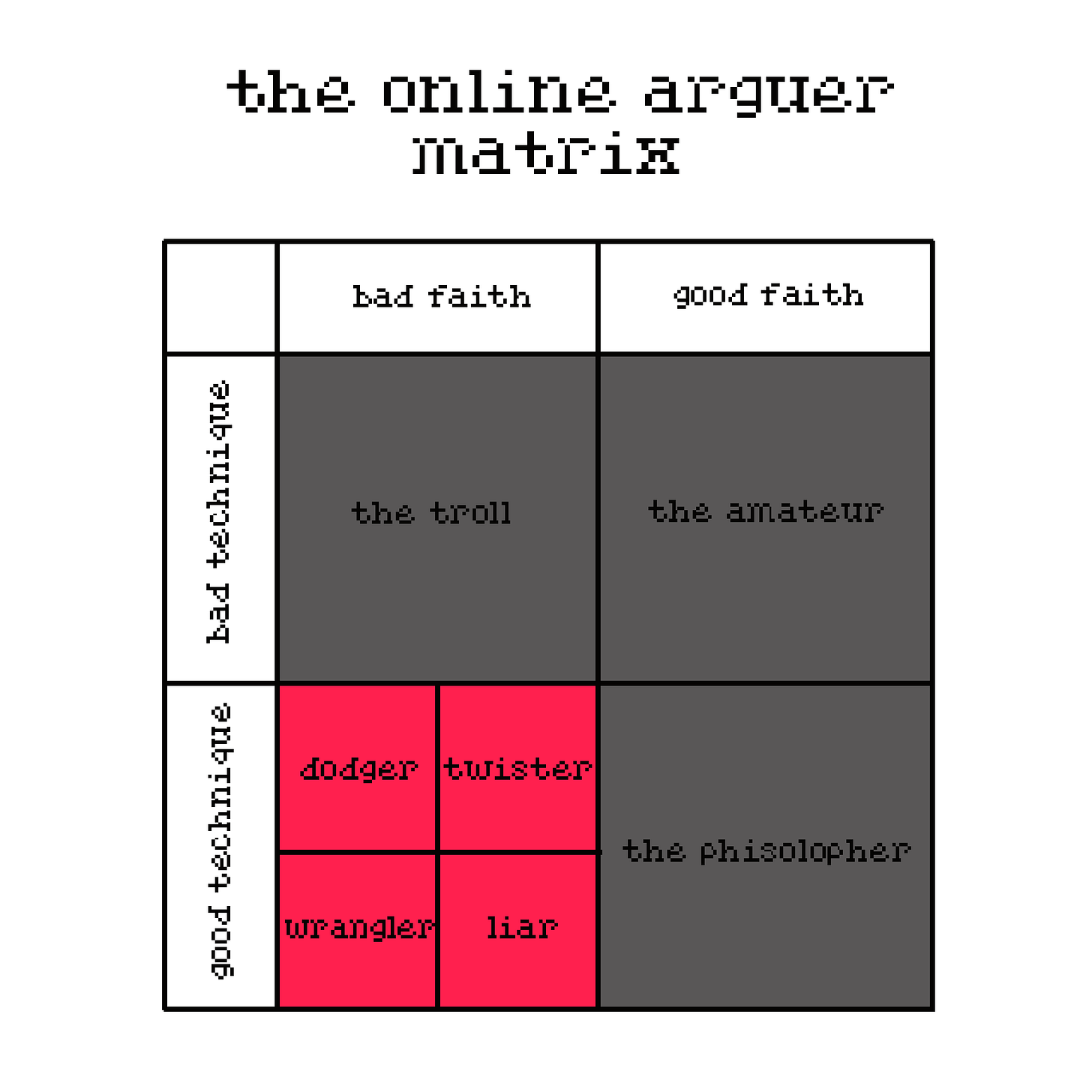

3. dirty tactics

Alright, so we’ve covered how to handle the different personalities in a debate. The Philosopher? Just hit them with facts and logic. The Amateur? Guide them in the right direction. The Troll? Ignore and move on.

But then there’s the Manipulator. How do you correctly deal with them? And that’s where things get tricky.

So let’s talk about them.

According to two-time world debate champion Bo Seo, he resolved to list the common tactics that are used by bad faith arguers. The four common personas he came up with were:

the dodger

the twister

the wrangler

the liar

a. the dodger

You say, “We need to do something about wealth inequality—it’s getting out of control.”

The dodger, instead of engaging with your point, does what they do best: sidestep the actual argument.

"Oh, so you think people shouldn’t be rewarded for hard work? Should we just hand out free money to everyone?"

See what happened? You were talking about wealth inequality. Now, suddenly, you’re defending whether any form of financial success is legitimate. Your original point is gone, buried under a new debate you never signed up for.

how to deal with it:

Don’t take the bait. Just calmly bring it back: “That’s not what I said. I’m talking about wealth inequality.” and highlight that they are trying to change what the disagreement is about

If you let them, the dodger will drag you through a maze of semi-related but completely off-track arguments until you don’t even remember what you were originally trying to say. Stay firm, or you’ll be debating capitalism vs. socialism before you even get to make your actual point.

b. the twister

You bring up wealth inequality. Instead of engaging, they dodge.

"Oh, so you think success shouldn’t be rewarded? Should we just start giving out free money?"

You were discussing inequality, but now you’re stuck justifying whether financial achievement is legitimate. Your original argument? Pushed aside in favor of a debate you never asked or was ready for.

how to deal with it:

Don’t follow their detour. Steer it back.

"That’s not what I meant. I’m talking about wealth inequality—let’s stick to that."

Point out their deflection. If you don’t, they’ll keep shifting the conversation until you’re arguing about something completely different. Keep your ground, or you’ll find yourself debating economic systems instead of the issue you actually raised.

c. the wrangler

No matter what you say, the wrangler finds a flaw. They poke holes, tear down ideas, and point out every possible downside—but offer nothing in return.

You propose a solution. They smirk. "That won’t work."

You suggest an approach. They shake their head. "That’s unrealistic."

Great. Now you’re stuck defending every possible imperfection while they sit comfortably on the sidelines, never committing to an idea of their own.

how to deal with it:

Flip the script.

"Alright, so what’s your solution?"

Make them take a stand for something. If they have a real position, they’ll have to defend it. If they don’t, they’ll fumble. Either way, you’ve broken the cycle—and suddenly, they’re the one under the spotlight.

d. the liar

A good liar doesn’t just drop one falsehood—they flood the zone. It’s not one misstatement, it’s an avalanche. Before you can debunk the first, three more roll in. Suddenly, you’re drowning in half-truths, distortions, and outright fabrications.

how to deal with it:

Don’t take the bait. You can’t fight a flood by chasing every drop of water. Instead, pick your spots.

Find one or two key lies—the ones that best expose their game. Then do a simple swap: take their falsehood, plug in the actual truth, and show how the whole argument crumbles.

Once you’ve replaced fiction with fact, you’re not just proving them wrong—you’re revealing the entire strategy for what it is. And when the audience sees the pattern, the liar loses their power.

the importance of engaging bad-faith actors

One of the most valuable things that knowledge and mastery of this kind of defense against bad-faith actors give us is the ability to challenge the bullies in our lives.

Some of that is a necessity—bullies exist, and they often bring the fight to us. But beyond self-defense, it’s crucial to engage with bad-faith actors early and, in many cases, often. The more they go unchallenged, the more their influence grows.

Even when we feel powerless in the face of a bully or a manipulative debater, we need the right tools to respond. More importantly, we need strategies to reset the conversation—to reclaim control and shape discussions in ways that promote truth, clarity, and fairness.

4. some last things before the real battle

If you’re stepping into an online debate, you need to be prepared—not just to argue, but to argue well. Most people don’t. They wade in with half-baked opinions, cherry-picked stats, and the emotional resilience of wet tissue paper.

You don’t want to be one of them. So, take out your notebook, before you start typing, here’s what you actually need to have in place.

a. strong sources

First, you need an arsenal of strong sources. If you don’t have receipts, you don’t have an argument. The internet runs on vibes more than facts, and if you want to cut through the noise, you need solid references.

The best sources are peer-reviewed journals, government reports, and reputable news organizations—basically, anything that went through a rigorous fact-checking process before publication. The problem? Most people won’t read them, and some aren’t even accessible without a paywall.

A good middle ground is well-sourced Wikipedia pages, research-based explainers from credible institutions, and expert interviews. What you don’t want to rely on are random blogs (this one for example), Threads without citations, or YouTube rants filmed in a car.

The realest thing you can do is to anticipate counterarguments. If you already know the weak spots in your case, you can fortify them before anyone else even gets a chance to poke holes.

b. emotional control

Next, you need emotional control and stamina. The longer an argument drags on, the less it becomes about truth and more about endurance.

I realized this when I watched someone I have the honour to disagree with spend three days straight locked in the same debate—without adding anything of actual value. Just a whirlwind of fallacies, baseless assumptions, and sweeping generalizations.

At some point, you have to accept that some people aren’t worth the engagement. They're not arguing to understand; they’re just running in circles, and you’re the one getting dizzy.

You have to recognize when a debate is actually worth engaging in and when it’s just a time-sink. If someone keeps twisting your words, moving the goalposts, or refusing to acknowledge basic facts, they’re not debating in good faith—you’re just wasting energy.

It’s also crucial to avoid ego traps. If you find yourself arguing just to “win” rather than to actually make a point, you’ve already lost. The best debaters stay calm while their opponents spiral, which makes them look even more credible.

And most importantly, don’t let anger do the typing. Some of the worst arguments happen when emotion takes over, and you end up saying something impulsive that you regret later. If you feel yourself getting too heated, step away. The internet isn’t going anywhere.

c. block and disengage

Finally, you need to know when to block and when to ignore. Blocking isn’t cowardice—it’s strategy. Think of it as clearing the battlefield of distractions. If someone is trolling, engaging in personal attacks, or deliberately misrepresenting your points, blocking them isn’t a weakness—it’s efficiency.

There’s no rule saying you have to waste time on bad-faith actors. However, there are also moments where engaging is worthwhile. If the other person is genuinely open to discussion (even if they disagree), or if you’re in a public thread where bystanders might benefit from seeing the debate play out, it can be worth staying in the conversation. Sometimes, even a losing argument can sharpen your thinking for the next battle.

A strong debater doesn’t just fight for the sake of fighting—they know when to strike, when to hold back, and when to walk away. If you prepare well, argue with purpose, and manage your energy, you won’t just survive the battlefield of online discourse—you’ll own it.

conclusion

At the end of the day, “winning” an online argument is a bit like winning a staring contest with a goldfish — sure, you've technically triumphed, but no one really cares, least of all the goldfish. The fleeting satisfaction of proving someone wrong on the internet is like the thrill of snagging the last slice of pizza at a party — briefly glorious, yet ultimately hollow because it's still just pizza.

You might screenshot your victory, and share it with friends who'll give you a digital pat on the back, but deep down, you know the world has not been fundamentally improved by your prowess in virtual combat.

Perhaps the trick is balancing the urge to verbally annihilate someone with the awareness that no one actually reads 20-tweet threads anymore.

Maybe it’s less about “winning” and more about figuring out why we’re all so desperate to be right in the first place — and realizing that, sometimes, it’s okay to just let the goldfish win.

footnote

Brady et al. (2021) Brady, W. J., Crockett, M. J., & others. (2021). Likes and Shares Teach People to Express More Outrage Online. Published in Science Advances.

Suler, J. (2004) ‘The online disinhibition effect’, CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), pp. 321–326.

Bakshy, E., Messing, S. and Adamic, L.A. (2015) ‘Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook’, Science, 348(6239), pp. 1130–1132.

Bail, C.A., Argyle, L.P., Brown, T.W., Bumpus, J.P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M.F. et al. (2018) ‘Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), pp. 9216–9221.

Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1979)

An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin, W.G. and Worchel, S. (eds.) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47.

Suler, J. (2004) ‘The online disinhibition effect’, CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), pp. 321–326.

Munger, K. (2020) Online debates as ideological theater: How social media feedback reinforces group dynamics. Journal of Communication, 70(3), pp. 234–250.

Parsakia, R. and Jafari, A. (2023) Fandom and identity formation in online communities. Journal of Fandom Studies, 10(1), pp. 45–62.

I recently have a cool experience on threads. Like a person actually say oh wow, you have your point. I should have been more abc xyz. I was like wtf how is that legal. How can people be civil on this platform =)))

I do intend to make myself do a challenge. Daily reply 100 comments on thread/tiktok/youtube. Trying to be as constructive, informative and non-judgemental as possible. :">